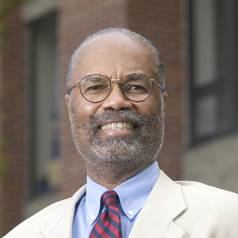

By Ronald Hall: Professor of Social Work, Michigan State University

Ronald Hall, Michigan State University

For generations, intimacy between black men and white women was taboo. A mere accusation of impropriety could lead to a lynching, and interracial marriage was illegal in a number of states.

Everything changed with the 1967 Supreme Court decision Loving v. Virginia, which ruled that blacks and whites have a legal right to intermarry. Spurred by the court’s decision, the number of interracial marriages – and, with it, the population of multiracial people – has exploded. According to the 2000 Census, 6.8 million Americans identified as multiracial. By 2010, that number grew to 9 million people. And this leaves out all of the people who might be a product of mixed ancestry but chose to still identify as either white or black.

With these demographic changes, traditional notions of black identity – once limited to the confines of dark skin or kinky hair – are no longer so.

Mixed-race African-Americans can have naturally green eyes (like the singer Rihanna) or naturally blue eyes (like actor Jessie Williams). Their hair can be styled long and wavy (Alicia Keys) or into a bob-cut (Halle Berry).

And unlike in the past – when many mixed-race people would try to do what they could to pass as white – many multiracial Americans today unabashedly embrace and celebrate their blackness.

However, these expressions of black pride have been met with grumbles by some in the black community. These mixed-race people, some argue, are not “black enough” – their skin isn’t dark enough, their hair not kinky enough. And thus they do not “count” as black. African-American presidential candidate Ben Carson even claimed President Obama couldn’t understand “the experience of black Americans” because he was “raised white.”

This debate over “who counts” has created somewhat of an identity crisis in the black community, exposing a divide between those who think being black should be based on physical looks, and those who think being black is more than looks.

https://www.instagram.com/p/vfQk7nlcyD/?taken-by=realcoleworld&hl=en

‘Dark Girls’ and ‘Light Girls’

In 2011 Oprah Winfrey hosted a documentary titled “Dark Girls,” a portrayal of the pain and suffering dark-skinned black women experience.

It’s a story I know only too well. In 1992, I coauthored a book with DePaul psychologist Midge Wilson and business executive Kathy Russell called “The Color Complex,” which looked at the relationship between black identity and skin color in modern America.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DOjgTIN9pTE?

As someone who has studied the issue of skin color and black identity for over 20 years, I felt uneasy after I finished watching the “Dark Girls” film. No doubt it confirmed the pain that dark-skinned black women feel. But it left something important out, and I wondered if it would lead to misconceptions.

The film seemed to suggest that if you are black, you have dark skin. Your hair is kinky. Green or blue eyes, on the other hand, represent someone who is white.

I was relieved, then, when I was asked to consult on a second documentary, “Light Girls,” in 2015, a film centered on the pain and suffering mixed-race black women endure. The subjects who were interviewed shared their stories. These women considered themselves black but said they always felt out of place, on the outside looking in. Black men often adored them, but this could quickly flip to scorn if their advances were spurned. Meanwhile, friendships with darker-skinned black women could be fraught. Insults such as “light-bright,” “mello-yellow” and “banana girl” were tossed at lighter-skinned black women, objectifying them as anything but black.

Identity experts weigh in

Some of the experts on identity take issue with the general assumptions many might have about “who is black,” especially those who think blackness is determined by skin color.

https://www.instagram.com/p/BO6SBURAj4n/?taken-by=logic301&hl=en

For example, in 1902 sociologist Charles Horton Cooley argued that identity is like a “looking glass self.” In other words, we are a reflection of the people around us. Mixed-race, light-skinned, green-eyed African-Americans born and raised in a black environment are no less black than their dark-skinned counterparts. In 1934, cultural anthropologist Margaret Mead said that identity was a product of our social interactions, just like Cooley.

Maybe the most well-known identity theorist is psychologist Erik Erikson. In his most popular book, “Identity: Youth and Crisis,” published in 1968, Erikson also claimed that identity is a product of our environment. But he expanded the theory a bit: It includes not only the people we interact with but also the clothes we wear, the food we eat and the music we listen to. Mixed-race African-Americans – just like dark-skinned African-Americans – would be equally uncomfortable wearing a kimono, drinking sake or listening to ongaku (a type of Japanese music). On the other hand, wearing a dashiki, eating soul food and relaxing to the beats of rap or hip-hop music is something all black people – regardless of skin tone – can identify with.

https://www.instagram.com/p/33u3siHZkb/

Our physical features, of course, are a product of our parents. Indeed, in the not-too-distant future, with more and more interracial marriages taking place, we may find black and white hair texture and eye and skin color indistinguishable. It’s worth noting that there’s an element of personal choice involved in racial identity – for example, you can choose how to self-identify on the census. Many multiracial Americans simply identify as “multiracial.” Others, even if they’re a product of mixed ancestry, choose “black.”

Perhaps true blackness, then, dwells not in skin color, eye color or hair texture, but in the love for the spirit and culture of all who came before us.

Ronald Hall, Professor of Social Work, Michigan State University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.