Free expression on TV and social media generates big ratings and even bigger online followings. Unscripted reality stars claim to bring their authentic expressions to the public through these channels.

Beyond influencing the court of public opinion, though, can reality stars wind up in legal trouble for these actions? By: Shontavia Johnson Professor of Intellectual Property Law, Drake University

Shortly after Independence Day, reality television personality Robert Kardashian Jr. served up fireworks of his own on Instagram and Twitter, posting embarrassing and lewd videos and photos of his ex, Angela “Blac Chyna” White, in an hours-long tirade. The evolving situation captured the media’s attention and, unfortunately for Kardashian, the posts also captured the attention of White and her lawyers.

In a matter of days, White and her legal team filed for, and received, a temporary restraining order against Kardashian based on his social media posts. According to White’s lawyers, they received a “complete and total victory” in the civil case. White has also threatened to press criminal charges under California’s revenge porn laws.

While the exhibits in the case have been sealed, the order prohibits Kardashian from, among other things, posting pictures online of White and their infant daughter.

This saga is the latest high-profile example of the serious legal issues revolving around both reality TV and social media. To the general public, TV footage and social media posts can seem like easy proof of behavior. However, as a law professor who researches the impact of the internet on our legal system, I’ve learned that using this information as evidence in court is not always a slam dunk.

Repercussions of reality TV

Reality TV provides us unprecedented access into others’ lives – and creates novel legal problems for people who find themselves in court. As TV cameras have begun to give us seemingly unfiltered views into the private lives of others, they’ve also captured information that could be used in legal proceedings.

This kind of programming has roots in the “Candid Camera”-type shows that started in the 1940s and the groundbreaking “An American Family” documentary series that aired on PBS in 1973. But reality television really exploded in popularity toward the beginning of the 21st century. Today, there are nearly twice as many reality TV shows as there are scripted shows during prime time. Viewers tune in to see what traditionally has taken place behind closed doors. With the rise in prominence of such shows and their stars, it’s no wonder that reality TV footage is increasingly showing up in court.

Some early cases of reality TV footage being used in courtrooms revolved around civil cases. In one famously contentious lawsuit between actor Ryan O’Neal and the University of Texas, the school tried to use TV footage from the reality show “Chasing Farrah” to prove that O’Neal did not own an Andy Warhol portrait of Farrah Fawcett. The university had a vested interest in the portrait because when Fawcett died, she left it all of her artwork. O’Neal argued that he owned the portrait because Warhol gave it to him during Fawcett’s life.

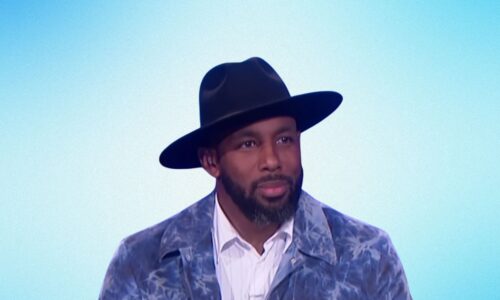

Ethan Lundgaard, CC BY

In “Chasing Farrah” footage, Fawcett tells the owner of an auction house that she owned two Warhol portraits – including the one O’Neal claimed was his. The university argued this proved that Fawcett, not O’Neal, was the rightful owner of the portrait. But even with this footage, O’Neal won the lawsuit and the court allowed him to keep the portrait.

Footage used in criminal cases has not always fared better. For example, “To Catch a Predator,” a reality TV series on from 2004-2007, focused on exposing men who solicited sex online from underage decoys. Though this footage appeared to show men committing horrible acts and being arrested, it did not always lead to convictions in court.

For example, one California man who appeared on the show was acquitted of all charges because the judge did not find the evidence credible. Interestingly, he was the only man from his episode who went to trial – all of the other men from that same California location pleaded guilty without taking their chances in court. In another instance, a Texas district attorney dropped all charges and refused to prosecute any of the 24 men featured on the program from his district; he questioned the involvement of people outside of law enforcement and the unreliability of the evidence they gathered.

What’s really real

Social media, on the other hand, has at times been used more successfully in court, though it’s not automatically admissible. Before a judge allows a social media post to be considered, it must be “authenticated” – a lawyer needs to show that the alleged wrongdoer owns the account and wrote the post in question, and that the printed-out version before the court accurately reflects what appeared on the social media site.

States have different rules for proving this. In Maryland, for example, authentication standards are very high to avoid the risk of manipulation, and courts request detailed evidence of proof. In other states, like Texas, while the judge serves as a gatekeeper for the evidence, the jury gets to make the final decision about how reliable social media evidence is.

Once social media posts are admitted as evidence, however, they can be helpful for the submitting party. In one recent case, Bollea v. Gawker, Hulk Hogan’s lawyers used conversations held by Gawker employees on Campfire, a social media messaging app, to prove claims of harm. Ultimately, a jury found Gawker liable for US$140 million in damages related to its posting of a sex tape featuring Hogan.

Social media posts have also led to the largest gun bust in New York City’s history, driven a settlement between department store Lord & Taylor and the Federal Trade Commission over charges of deceptive Instagram posts and affected child custody decisions made by courts.

![]() Our very public and very interconnected world has made it easy for celebrities and noncelebrities alike to memorialize private acts in a very public way. Reality TV footage and social media posts are already changing what counts as legal evidence as courts grapple with just how “real” it all is. It’s still unclear whether society’s penchant for voyeurism – and the way we now live our lives so publicly – will have an effect on how we behave outside the courthouse.

Our very public and very interconnected world has made it easy for celebrities and noncelebrities alike to memorialize private acts in a very public way. Reality TV footage and social media posts are already changing what counts as legal evidence as courts grapple with just how “real” it all is. It’s still unclear whether society’s penchant for voyeurism – and the way we now live our lives so publicly – will have an effect on how we behave outside the courthouse.

Shontavia Johnson, Professor of Intellectual Property Law, Drake University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

![]()