Cheryl Thompson, Toronto Metropolitan University

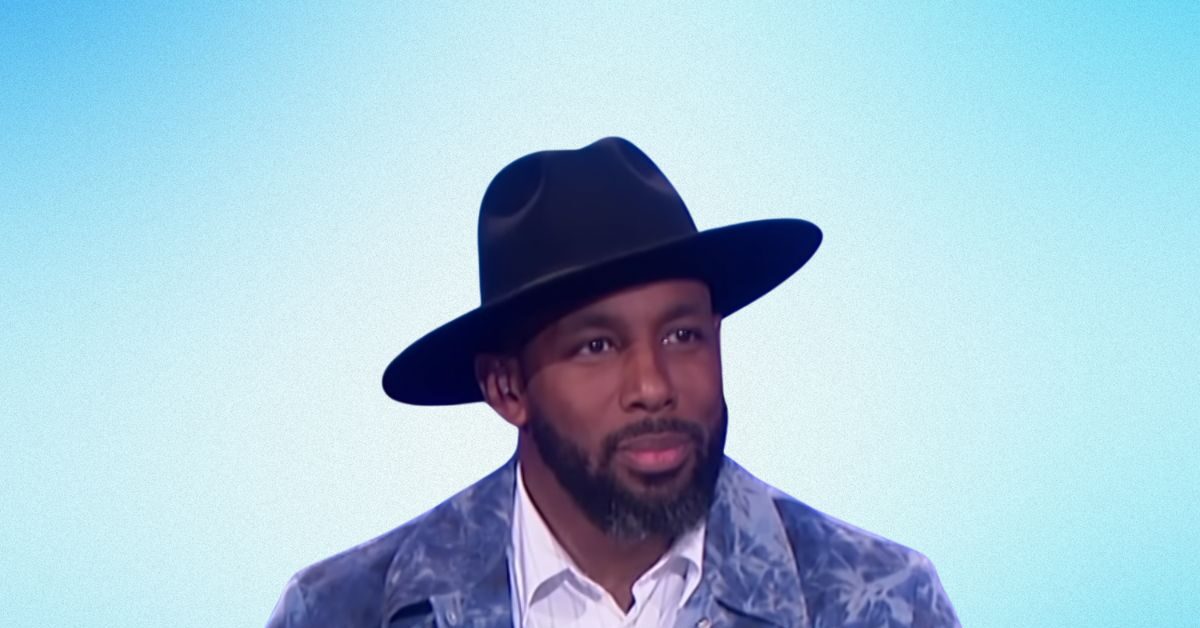

Last week, dancer and DJ Stephen ‘tWitch’ Boss died from suicide at age 40. Like many, I was incredibly shocked and saddened by the news.

As a scholar of Black entertainment history, I also reflected on the longer history of Black male entertainers dancing or telling jokes to their deaths despite cultivating a public image as “pure love and light,” which is how tWitch’s former co-producer, Ellen DeGeneres described him on her Instagram upon hearing of his death.

There have been so many tragic and unexpected deaths of young Black men in the entertainment industry that websites, such as BestOfDate, and Ranker have formed to document them.

While these sites are primarily documenting the deaths of rappers, they are also creating a narrative around Black men that values their personas more than the lives they actually lived.

If there is a common thread running through the seemingly unexpected deaths of Black male celebrities, it’s that few around them were made aware of their struggles. When singer-songwriter Prince died in 2016 at 57 from an accidental overdose of fentanyl, even his closest friends did little to address his drug addiction. Similarly when Chadwick Boseman, actor and star of Black Panther died of Stage 4 colon cancer in 2020 at age 43, no one in the industry knew that he had been battling the disease. While these deaths were given a medical cause, I believe the larger issue of Black male celebrities not talking about their struggles plays an undeniable role.

When a celebrity’s image matters more to the public than their real-life challenges, it is often referred to as the parasocial relationship.

How parasocial relationships have changed

First coined in 1956 by sociologists Donald Horton and R. Richard Wohl, the “para-social interaction,” was a kind of psychological relationship experienced by how television audiences related to performers. Today, parasocial interactions apply to social media platforms. As audiences are repeatedly exposed to media personas, we develop illusions of intimacy, friendship and identification.

They’re at our fingertips and in front of our eyes every second of every day. Clinical psychologist Bethany Cook told Stylecaster that “social media allows the untouchable to become touchable.”

And the lines between reality and fiction are increasingly more blurred than when Horton and Wohl conducted their study.

In reality, the networks of intimacy that we develop with celebrities are based on impersonal forms of communication.

For example, two days before tWitch died, he posted a dance video to his Instagram with his wife, Allison. While dancing Instagram posts come off as pure fun, they are mostly a marketing strategy to increase brand awareness, not an innocent glimpse into a dancer’s “off-time.”

Today’s celebrity and performer are involved in the curation of webs of intimacy and presumed friendships which makes it difficult to see reality. For example, when a celebrity we follow is struggling with a mental health issue.

Significantly, there is a long history of Black male performers burying mental health issues until they tragically and unexpectedly die.

Black men have been dying on-and-off stages for centuries

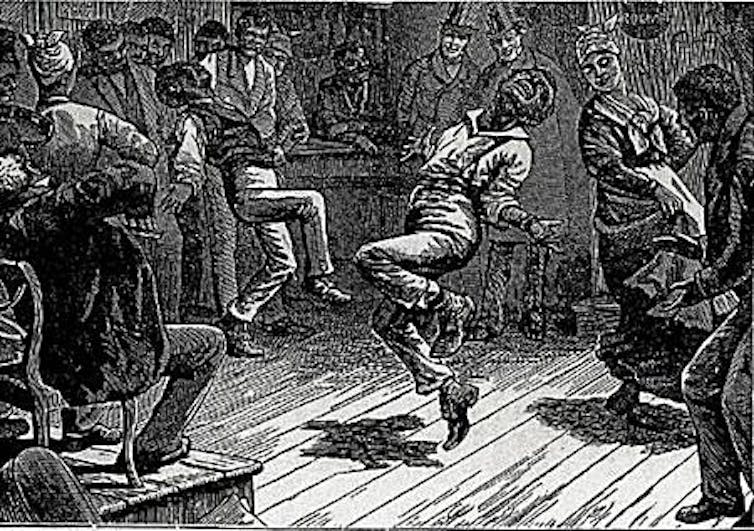

William Henry Lane (1825–1852), also known as Master Juba, was the first Black dancer to reach international acclaim on both sides of the Atlantic. Born in Providence, R.I., he is remembered not only as the originator of African American tap dance but has been hailed as “the Jackie Robinson of the American stage.”

William Henry Lane (‘Master Juba’) dances in New York’s Five Points District as Charles Dickens and a companion watch in the background. (Engraving from American Notes by Charles Dickens, 1842: The Penumbral Frontier: Landscape, Modernity, and the Subterranean Imagination in New York City Literature and Culture), CC BY

By the 1840s, Lane was billed as one of the greatest dancers of his time, no small feat if you consider that throughout the 19th century (and most of the 20th), Black performers did not get regular work unless they fit themselves into the mold cast for them by white casting directors.

However, because it was the 19th century, Lane was often forced to wear the burnt-cork mask of blackface minstrelsy, as he danced. As the sole Black performer on white stages, Lane worked day and night for 11 years in Britain until he died at only 27 years old.

As cultural sociologist Michael Pickering observes in Blackface Minstrelsy in Britain, by most accounts, Lane “had quite literally danced himself to death.”

tWitch was one of the first Black dancers on So You Think You Can Dance to catapult into the mainstream. His unique combination of personality and hip hop moves made him one of the most memorable and beloved members of the show.

While the reasons tWitch took his life are still unknown, the legacy of Lane’s death, which was the result of physical and mental exhaustion lingers eerily in his passing.

It’s time to listen to the whisper

At the end of my book, Uncle: Race, Nostalgia, and the Politics of Loyalty, I write that “Uncle Tom is our collective whisper.” Meaning that when Black men are always smiling, happy, loyal and constantly performing, that state of “on-ness” comes at a cost.

Redd Foxx in 1966. (John E. Reed/Coast Artist Management0

In centuries past, working oneself to death meant that performers died suddenly like Lane or the legendary comedian Redd Foxx, who suffered a heart attack on set in 1991 after working in the industry for 56 years. The trailblazing dancer, actor and choreographer Gregory Hines, who revitalized tap dance in the 1980s, also died young at age 57 after a short battle with cancer.

Today, it is more likely that Black celebrities — especially those who make a career of entertaining primarily white audiences — suffer in silence until they die suddenly, take their own lives and/or have violent public outbursts.

The “slap heard around the world,” for instance, at the 2022 Oscars was not just about two Black male entertainers having an inappropriate altercation; it was a glimpse into Black mental health where the cost of playing the “nice guy,” as Tayo Bero argued in a piece for the Guardian, takes an often-invisible toll.

Democratic presidential candidate Hillary Rodham Clinton, right, practices her dance moves with DJ Stephen ‘tWitch’ Boss during a break in the taping of ‘The Ellen DeGeneres Show’ in 2015. AP Photo/Mary Altaffer)

A 2015 report by the U.S. National Center for Health Statistics found that only 26.4 per cent of Black and Hispanic men ages 18 to 44 who experienced daily feelings of anxiety or depression were likely to have used mental health services, compared with 45.4 per cent of non-Hispanic white men with the same feelings.

The Mental Health Commission of Canada reports similar disparities noting that between 2001 and 2014, 38.3 per cent of Black Canadians with “poor or fair self-reported” mental health used mental health services compared with 50.8 per cent of white Canadians.

Black male celebrities who are chasing white approval are self-destructing in front of our very eyes. The whispers have become non-stop noise. It’s time for celebrities with power to do more than post condolences on social media. They need to be part of the process to create sustainable structures and supports for Black men in the industry. When that happens, the parasocial relationship might be key to changing lived realities.

My hope is that Stephen ‘tWitch’ Boss’s death does not overshadow the life he lived. And that the entertainment industry finally breaks down the wall of shame that keeps too many in the closet about their mental health struggles.

If you or someone you know is struggling with suicidal thoughts or mental health matters, you can get help here: Talk Suicide Canada: 1-833-456-4566 (phone) | 45645 (text between 4 p.m. and midnight ET)

Cheryl Thompson, Assistant Professor, Performance, Toronto Metropolitan University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.