Sanya Osha, University of Cape Town

There’s a lot of hype around amapiano. The South African dance music genre has dominated dancefloors since 2019, spreading from South Africa to West Africa and now to the world. But it’s time to peer through the hype and see if amapiano is able to transition from a cloistered club scene onto a truly global stage in terms of performance strength, conviction and credibility.

Kabza de Small, DJ Maphorisa, Major League DJz, DBN Gogo, Lady Du … the list of amapiano stars is growing. Undoubtedly, though, there are concerns regarding the live performances of many. Beyond the gimmicks of slick studio technology and computer wizardry, it appears that many really struggle to make an impact on stage. Surely, the questions of stage presence, control and frontsperson desirability are significant in any music genre’s ultimate global success. Just ask US stars Beyoncé, Lady Gaga and Rihanna or Nigeria’s Burna Boy.

Amapiano’s DIY sensibilities, freshness and underdog status are some of its apparent heartwarming qualities. However, amapiano musicians rarely perform with live bands. Their globally streamed performances are often marred by technical problems, poor sound quality and an evident lack of professionalism. Many acts appear under-rehearsed.

The question is, to what extent will this be a limiting factor in amapiano’s ascendancy to higher levels?

What is amapiano?

Emerging from the largely urban Gauteng province in South Africa as early as 2012, amapiano is today waxing stronger than ever as artists establish multiple digital platforms and spaces. Music executives are jostling to see how all of this might translate into mega bucks and business.

Amapiano is overwhelmingly deejay-driven, with infectious and often melodic beats interlaced with bluesy, jazzy interludes that are punctuated by the ubiquitous log drum (programmed electronic drumbeats that sound natural).

Growing from local experiments, amapiano is also ultimately derived from US house music, which never transcended into the mainstream. Unlike funk, punk and grunge, which have become staples of the US music market, house music had to find its way to South Africa and places like Ibiza in Spain to gain fresh wings.

In South Africa, at the dawn of democracy in the early 1990s, house music became the euphoric soundtrack for party-loving youngsters whose main wish was to dance the night away. It seemed they wanted to forget the horrors and bleakness of the apartheid years. And so they plunged themselves into an experimental social and music environment that promptly birthed kwaito and other house music subgenres – the city of Tshwane spawned Bacardi house and Durban birthed gqom.

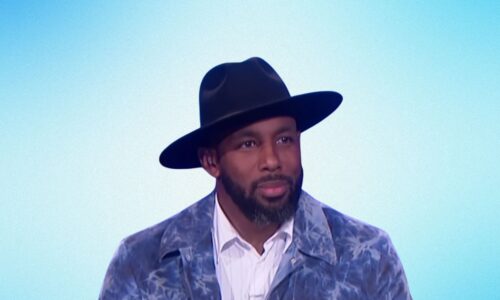

Kabza De Small and DJ Maphorisa demonstrate amapiano’s West African reach.

South Africa has become a global leader in producing the most delectable waves of electronic dance music. Amapiano pioneers such as De Mthuda have called it a lifestyle or movement just like hip-hop.

With the global ascendancy of West African Afrobeats, perhaps it was only a matter of time for South Africa to provide its own music equivalent.

Amapiano provides a golden opportunity to feel good and create a seemingly endless array of dance moves such as the famous “pouncing cat”, characterised by the twisting of the wrists in a circular motion in unison with outwardly kicking legs.

The big names of the amapiano genre – such as Kabza de Small, DJ Maphorisa, De Mthuda, Major League DJz, DBN Gogo, Mas Musiq, Mr JazziQ, Focalistic, Musa Keys, Mellow & Sleazy, Josiah De Disciple and Lady Du, among a continually evolving mass of producers, beatmakers, rappers and singers – still appear to be second rate performers on a global scale. This could limit its eventual crossover appeal.

Performance issues

One of South Africa’s most energetic performers has got to be rapper Cassper Nyovest. His fill-up-the-stadium endeavours and huge fanbase have obviously brought out the performance beast in him. There you have your star live performer.

Things don’t look so good on the performance front for amapiano stars. Kabza de Small is mostly staid behind the decks. The same can be said for most of the genre’s beatmakers and producers. Even the highly influential Maphorisa is much better behind the decks than when attempting to woo a delirious throng on stage.

Lady Du performs in Johannesburg.

Lady Du’s performance at the crammed Boiler Room x Ballantine’s True Music Studios in Johannesburg this year should be a cause for concern about the range and possibilities of today’s amapiano luminaries. Her act looks and feels raw and amateurish. She, like many current amapiano rappers and singers, has no album to her credit yet (though media reports indicate one is coming). During her performance, she ad-libbed to other musicians’ songs she’d featured on. Indeed, she attained her status on a string of features, not a coherent body of work. Big names in the scene such as Sir Trill, Daliwonga, Malumnator, Toss, Sino Msolo and others are in a similar situation.

Amapiano’s heavy reliance on producers and beatmakers is revealing. Few rappers and singers are able to manoeuvre the decks with convincing skill and they have to rely on beatmakers. This is a characteristic of much contemporary music.

The good news

However, there are a few performers who merit watching keenly. TxC a Gqeberha-born deejay duo, recently released an EP, A Fierce Piano, featuring amapiano heavyhitters. They look good and move well but it remains to be seen if they can truly work a crowd or stand as bona fide musicians.

Another promising performer is Young Stunna, an award-winning rapper and singer. He’s able to convert his amazing vocal prowess to live wire stage performances, setting benchmarks to which other performers might aspire.

Amapiano is a youth powered movement that provides often despondent young South Africans with considerable optimisim, bonhomie and creative opportunities. It injects a belief in self and a drive to want to take on the entire world through the seduction of hypnotic beats. Time will tell if they do.

Sanya Osha, Senior Research Fellow, Institute for Humanities in Africa, University of Cape Town

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.